If you grew up enjoying the American circus, you can thank Iowa.

While the Hawkeye State didn’t host the first circus on US soil—that honor goes to Philadelphia—Iowa played a key role in the industry’s development and is directly connected to “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

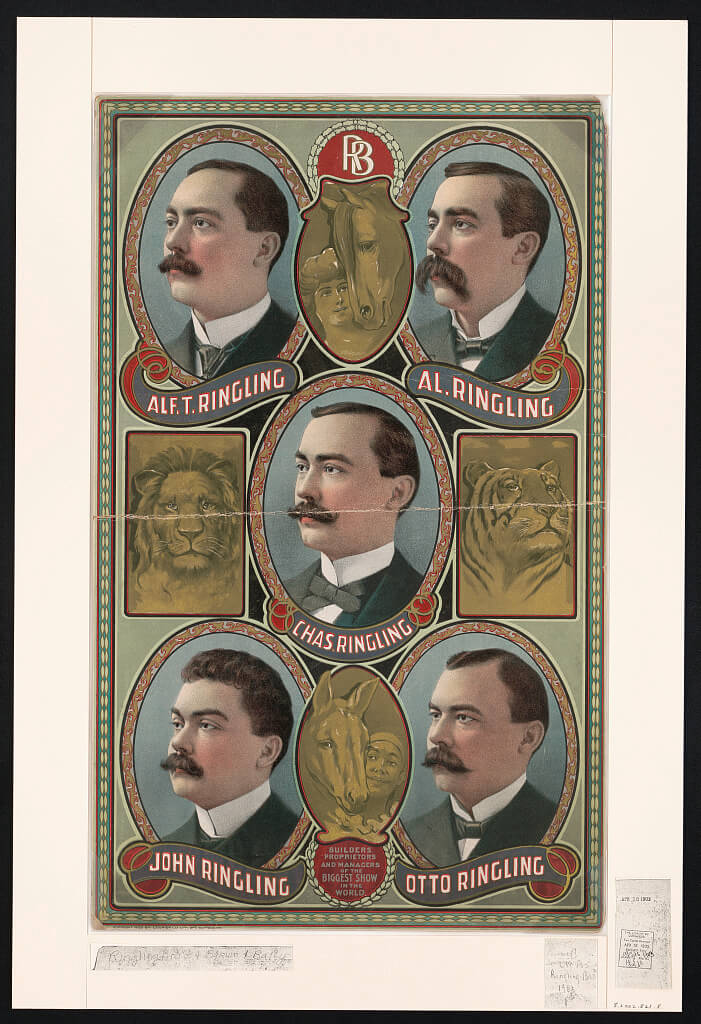

Four of the seven Ringling Brothers—as in Ringling of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus fame—were born in McGregor, Iowa, a Clayton County community nestled on the banks of the Mississippi River.

The Ringling family eventually moved across the river to Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, although they didn’t launch their circus until they were settled in Baraboo, Wisconsin, which later became home to the Circus World Museum.

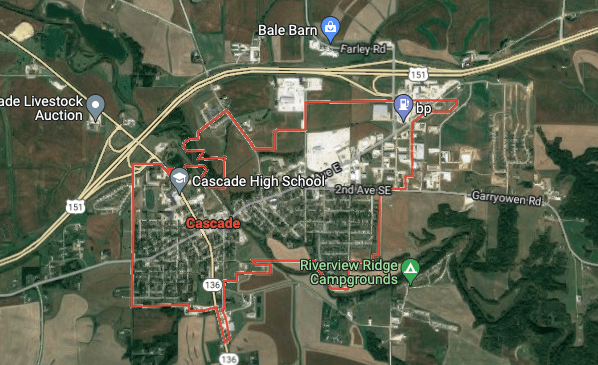

In 1884, five of the Ringling brothers started what would go on to become their famous family franchise. A big reason the early circus was able to survive was because of the townspeople of Cascade, Iowa.

The small Dubuque/Jones County city is credited with helping the circus out during a pinch and to this day—Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey stopped touring in 2017, but plans to return in fall 2023—Cascade residents get free admittance to shows.

According to Cascade lore, the circus ran into a nasty storm system on its way to Onslow, Iowa, that ripped up its tent and “ruined their already meager equipment.” The circus was unable to perform and couldn’t afford to feed its animals either. Some local feed store owners kept a few of the circus animals until the Ringlings could afford to pay for their food.

To try to make up for their loss, the circus and what animals they had available made the 15-mile trek to Monticello.

Here’s how the city of Cascade’s website describes that moment:

“They entered Monticello bedraggled and penniless, but the Ringling Brothers were still hopeful that with a show to one good crowd, they could get back on their feet. Their hopes fell flat in Monticello because they had no money to purchase the license which the city required in order for the circus to perform.”

This is where Cascade comes into play. Al Ringling, the show’s producer and the oldest sibling, heard Cascade enjoyed live entertainment and went to visit the community. (Side note: Is there a place in America that didn’t enjoy live performances in the 1880s? I mean there wasn’t much else going on.)

Luck was on his side because, according to the Tri-County Historical Society, Al Ringling “met with and made friends with two prominent Cascade citizens, Isaac W. Baldwin and RJ McVay. Isaac Baldwin held two prominent positions; he was the mayor of the town and the publisher of the town’s newspaper. RJ McVay did Cascade’s banking privately as there was no formal bank at the time.”

Baldwin issued the circus a permit free of charge and printed out handbills to advertise the show on credit. McVay advanced the circus the money necessary to bring the rest of the troupe to Cascade, pay for the animal feed, and take care of other expenses.

Additionally, several Cascade boys offered to help bring the circus to town over the muddy roads. After a couple of days, the tent was set up, and Cascade hosted a full house for an afternoon circus show.

The story gets even better.

“The Ringling Brothers were pleased, but there was more to come,” reads the city’s historical account. “A crowd swept in from the countryside to see the much advertised evening performance. So many people came that there simply wasn’t room for them all.”

The circus was able to make enough money from its performances in Cascade that it was able to repay its debt and still have funds leftover.

However, when the circus transitioned to rail transport—crisscrossing muddy Iowa roads with wagons would motivate anyone to look for a better system—it couldn’t return to Cascade because the city didn’t have an adequate rail line.

Here’s what happened next, according to the historical society:

“Several years after the Cascade performance, a group of Cascade friends, ‘Shorty’ Parrott, Ad Severence and Frank Snowden went to see The Ringling Brothers Circus performance in Monticello. They listened as Al Ringling captivated the crowd with his extravagant depiction of the wonders of the circus.

“They were startled as Al suddenly interrupted his speech to exclaim, ‘Why, there’s Shorty and some of the boys from Cascade. Come up here on this platform!’ He enthusiastically shook their hands and described to the crowd how Cascade helped the circus. Al Ringling said, ‘Anyone from Cascade is free to this show anytime. These boys will be at the door to identify anyone from Cascade and pass ‘em in. That goes for any place we may show on this earth. Anyone from Cascade has the run of the grounds wherever we are.’”

This remained true throughout the circus’ history. Former Des Moines Register columnist Kyle Munson confirmed in 2013 that the circus—Ringling Bros. purchased the Barnum & Bailey Greatest Show on Earth in 1909, creating Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey—still honored that pledge, but his column also pointed out something I also noticed.

According to the city of Cascade, it saved the circus in 1880. Most historical accounts say the Ringling Bros. circus formally began on May 19, 1884.

Uh oh.

By all accounts, the Cascade story is true—hence the continued free admission for Cascade residents for performances in Iowa—but the city’s recollection of when it happened might be a tad off.

Munson tried to get to the bottom of it while working on his column, but was unable to verify an exact year. One of his sources speculated that the famous Cascade performance took place on Aug. 17, 1885, which is also two days after the troupe performed in Monticello.

The Aug. 14, 1885, issue of the Cascade Pioneer has a preview for the Aug. 17 show. The brief in the paper also notes that “they [Ringling Bros.] come well recommended by the press throughout the state.”

This tidbit is also backed by a clipping in the Aug. 20, 1885, issue of the Monticello Express newspaper.

Additionally, 1885 is the earliest reference to “Ringling” I can find in the Pioneer’s archives, although there are clippings that mention “circus” dating back to 1880. It should also be noted the use of “circus” to describe ridiculous events seemed to be pretty common back then.

Like Kyle Munson before me, I gave it my best shot to figure out exactly when Cascade residents saved the circus, but I was unable to deduce a precise year. (I’m leaning toward 1885.) However, the other big question that remains is how many Cascade residents plan to take advantage of free admission to a Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey performance when the troupe returns in 2023?

by Ty Rushing

06/01/22