You may have heard the phrase “right to work,” as in, “Iowa is a right-to-work state.”

But what does right-to-work mean, and how does that government policy impact you as a worker?

“I think most of our members don’t exactly know,” said Charlie Wishman, president of the Iowa Federation of Labor AFL-CIO. “A lot of people get at-will employment [where an employer can fire you for any non-discriminatory reason] confused with right-to-work.”

How right-to-work began

Unions, which organize collectively to increase worker power, have always been a threat to the ones who have the power currently—the bosses, CEOs, shareholders, etc. And those bosses got pretty worried when Congress passed the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, part of the worker-friendly New Deal.

With increasing worker power on the rise, in 1947, corporate types managed to get Congress to pass (and then override a presidential veto of) the Taft-Hartley amendments to the Act, which allowed states to prohibit unions from requiring a worker to pay dues.

But there was intense opposition across the country to such laws including in Iowa, according to Wishman. He cited information from the IFL’s “A History of the Labor Movement in the United States,” written by David Colman and published in 2000.

Approximately 100,000 Iowa workers went on a one-day general strike on April 22, 1947, to protest Taft-Hartley. Around 50,000 of them attended a rally at the State Capitol in Des Moines to protest the state’s proposed right-to-work bill.

“There were a lot of folks who were very much opposed to it,” Wishman said. “And the governor [Robert Blue, a Republican] did not care.”

Iowa passed a right-to-work law the same year, one of the first states to do so. We’re now one of 26 states with such a law on the books.

What does right-to-work mean?

Right-to-work, broadly, is the “right” not to join a union or pay union dues, while still benefitting from the union’s presence at your workplace.

“What it means is it’s really about whether or not you can bargain,” Wishman said.

Let’s say you work at ABC Company, and workers at ABC are covered under an employment contract negotiated and enforced by the Unionsters.

Unless you’re a manager or supervisor, that contract also covers you, regardless of whether you’re a member of the union—meaning you get the same raises, bonuses, paid time off, and retirement as everyone else.

As a labor union, Unionsters helps workers bargain when the contract is up, represents you when you have a grievance against ABC, and can even pay you if you go on strike.

But in a right-to-work state like Iowa, workers do not have to be a member of Unionsters to reap all of those benefits.

“Right-to-work is very, very clever framing. It doesn’t really give anybody the ‘right’ to work at anything—everyone has a ‘right to work,'” Wishman said. “What it does is it diminishes the power of unions.”

Divided=easier to exploit

Right-to-work makes it seem like the law benefits you. After all, if you don’t have to pay union dues, that’s more of your paycheck in your pocket, right?

Let’s use the example of local taxes. Everyone who lives in your town has to pay for roads and schools. But if you didn’t have to pay taxes if you didn’t want to (right-to-live?), that’s thousands of dollars back in your pocket.

Except, that’s thousands of dollars that your town is now missing that won’t go toward reconstructing the roads.

Your town won’t miss a few thousand dollars. But if everyone’s allowed to opt out, while still getting the benefits, why would anyone pay taxes? Now your town IS missing that money.

Without those funds, the roads start crumbling, making your drive treacherous. You’re more likely to hit a pothole and bend a tire rim. Now, you’re spending those thousands on fixing your car—and the roads STILL aren’t being fixed, because there’s no longer enough money to do so.

You’re not saving money, as it turns out. You’re poorer. And now, your roads suck, too.

In other words, making taxes optional makes it more likely the entire tax system stops working as intended.

And that’s similar to what’s happened with unions over the last several decades in right-to-work states: Fewer incentives to join or form a union means fewer workers doing so, letting bosses dictate contracts individually and pushing wages and benefits down.

“If you’ve got much much smaller numbers [in your union], it’s going to be a lot more difficult when it comes to negotiation because they know that solidarity, that strength in numbers, the idea that everybody is gonna stay out together, isn’t there,” Wishman said. “And the company knows this. They know how to divide people.”

The Economic Policy Institute found that right-to-work states paid workers 3.2% less than states without those laws. Such workers also were less likely to have employer-sponsored health care and pension coverage.

“RTW laws have nothing to do with whether people can be forced to join a union or contribute to a political cause they do not support; that is already illegal,” EPI noted. “Nor do RTW laws have anything to do with the right to have a job or be provided employment. At their core, RTW laws seek to hamstring unions’ ability to help employees bargain with their employers for better wages, benefits, and working conditions.”

Koch Brothers behind right-to-work

Fewer incentives to join or form a union means fewer workers doing so, giving more power back to bosses—exactly as those aligned with corporate interests designed it.

So it’ll absolutely shock you to learn the Koch brothers are involved.

The nation’s right-wing backers of American capitalists have funneled millions of dollars to the National Right to Work Committee (NWRC) and its associated legal defense fund, which provides legal backing to workers wanting to get out of paying union dues.

That legal defense fund has been at work in Iowa as well: This spring, four workers at air filter manufacturer Donaldson in Cresco got several months’ worth of dues back from the United Auto Workers after a settlement. That lawsuit won the four workers “nearly $1,000” in total.

NWRC claims dues payments are excessive and democratically elected union representation is “corrupt.”

How much are union dues, anyway?

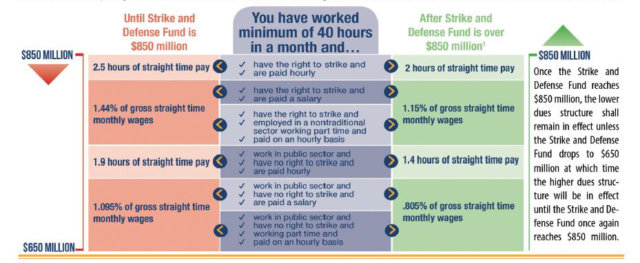

UAW dues are largely dependent on what rights certain workers have—if they have fewer rights, they pay fewer dues—but at the maximum, workers pay the equivalent of 2 1/2 hours of pay per month.

If you make $15/hour working full time and have the right to strike, AND the union’s strike fund was low, you’d pay a maximum of $37.50 per month in dues, or $18.75 per pay period, roughly.

That structure is similar at other large labor unions, like Teamsters or the International Association of Machinists, which includes a video on its site showing the breakdown of where dues payments go.

“From bargaining contracts to enforcing them through the grievance procedure, union dues provide the resources used by locals every day,” the UAW says on its website.

Members generally vote in democratic elections for a slate of officers who set dues, strike pay, and more.

Could right-to-work be overturned?

Yup. Just look to our Midwest cousin, Michigan.

The “pleasant peninsula” was late to the right-to-work party, only passing its law (called “freedom to work”) in 2012, which went into effect in 2013.

But when Michiganders elected Democrats to the majority last year—the first time that had happened in 40 years—repealing the law became a priority. Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer signed the repeal in March 2023. It goes into effect in March 2024.

Seeing the repeal of right-to-work there actually occur gave Wishman hope.

“That doesn’t happen by accident,” he said. “It happens through hard work. It happens through organizing.”

He sees the seeds of that work in Iowa over the last few years, notably the successful 2021 John Deere strike in Iowa as a big motivator.

Wishman added it will be young people in non-union industries leading the way, including Starbucks employees in Iowa City forming the first Starbucks union in Iowa, and Grinnell College students launching the first all-undergraduate worker union in the country.

“You have a whole generation of folks tired of the working world as it is right now,” Wishman said. “This is not an issue that’s going to go away.”

by Amie Rivers

5/23/23

If you enjoy stories like these, make sure to sign up for Iowa Starting Line’s newsletter and/or our working class-focused Worker’s Almanac newsletter.

Have a story idea for me? Email amie@iowastartingline.dream.press, or find me on Twitter, TikTok, Mastodon, Post, Instagram and Facebook.

Iowa Starting Line is part of an independent news network and focuses on how state and national decisions impact Iowans’ daily lives. We rely on your financial support to keep our stories free for all to read. Find ISL on TikTok, Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.

2 Comments on "What Does Iowa’s ‘Right to Work’ Law Mean?"

Workers should have the choice of whether or not they want to join a union. If they want to join- then great! However under no circumstances should it be mandatory.

For once I agree with Pat. With the following caveat: if you go to work for a place which has a union, you should have the opportunity to decline to join it. But if you do, then you shouldn’t get the benefits that the union negotiates for its members.